In the last post, I talked about the importance of the early conversations you have with your prospects. Ideally, you’ve dreamt a bit out loud with them, and you now have a good sense of the kind of future they’d love to see materialize. Now it’s time to price your work in a way that’s profitable to both your prospect and you—in that order.

This article is part of a 4-part series brought to you by Wix Studio about running valuable projects that grow your clients’ businesses and yours too. Wix Studio is a platform built for agencies and enterprises to create exceptional websites at scale. If you're looking for smart design capabilities and flexible dev tools, Wix Studio is the tool for you.

In this series

Quantifying value

If you’ve had value conversations with your prospect, you’ll likely have heard phrases about their desired future state that you can start to turn into a price. Some phrases are easier to convert than others. The easiest one is making more money.

The 6-Day Revenue Roadmap

A free 6-day email course for design freelancers and agency owners who need revenue fast—without a funnel, large audience, or fancy pitch deck.

Get Lesson #1 NowMaking more money

Imagine your prospect said that they can see a future where they’ve turned their current $1 million in annual revenue into $5 million in annual revenue. The value of this particular scenario—shorthand for “the total bounty able to be generated“—is $4 million. A well-positioned agency might envision a combination and sequence of services that might generate an additional $4M in revenue that include improving design, transitioning to a new e-commerce platform, and search engine optimization work.

The next question is how much to charge. I typically start at 10% of total value of the scenario, as it’s often small enough to the prospect to be a not-so-painful investment with a great return, and also large enough for me that it’s lucrative. For an opportunity that could generate $4M, I’d set my price at around $400k. If the prospect asks where I got that price, I’d be honest: “The opportunity seems to be generating $4M in additional annual revenue for you, and I typically start at 10% as I thought a 9× return on investment would be great for you and lucrative enough for me to keep my business running.” Every time I mention the price, I’m always sure to talk about it relative to the value. Saying “$400k” certainly induces sticker shock, but saying “$400k to create $4M of additional annual revenue” puts it in much-welcome perspective.

And the negotiations begin there.

Some clients may try to talk you down to 8%. Would you take $320k instead of $400k to generate $4M? For some, the answer is “heck yeah!” For others, they might prefer to keep 10% as their floor.

The type of negotiation I’ve found to be more common in this scenario, however, is that the prospect explores what it would take to negotiate you up. Because you’ve unearthed the idea that a 9× return on investment is on the table, they’ll often say something like, “If we were going for an additional $8M in revenue, does that mean you’d do that for $800k?” Regardless of your answer, what an amazing conversation to have with your prospect! Because you’ve spent the time and effort to dream with them across 4 conversations, they’re now starting to dream with you! It’s a world of difference from the kind of conversations where you’re sharing an hourly or weekly rate and doing simple multiplication to determine a fee.

Fuzzier forms of value

What if your prospect isn’t interested in making more money? What if they’re a non-profit? What if they’re a higher-ed institution? What if the work is about improving their market position? Those kinds of value are generally more difficult to quantify, but it’s certainly possible. All projects exist to bring about some change—more of something, or less of something—for the prospect; otherwise, it’s a vanity project, and I try to steer clear of those.

Assuming it’s not a vanity project, every change can be quantified and needs to be quantified in order for you and your prospect to have a shared articulation of the change so you can recognize it when it happens. Non-profits want more donors or a larger constituent base. Higher-ed institutions want more applicants. Enterprises want less overhead. In his book Pricing for Profit, Dale Furtwengler outlines 9 different things that buyers generally value: speed, friendliness, integrity, dependability, convenience, image, service, innovation, and knowledgeable salespeople. Every one can be quantified.

For example, Furtwengler describes how to quantify the value of improving a prospect’s image. He uses the example of clothing brands. People who shop at places like Nordstrom or Saks Fifth Avenue pay on average 10 times what they’d pay at a place like Walmart. Taking a prospect’s image from being the Walmart of their industry to being the Nordstrom of their industry might be in the zone of 10×-ing whatever it is that they’re doing, and you can start your price at 10% of that.

The point here is that these aren’t formulas. They are rationales for the starting point of conversations with your prospect. You might be wrong about how you’re quantifying value; let your prospect correct you. The important thing is that you’re constantly steering the conversation to talking about value.

Profit first

Once you’ve quantified the value of a project and a potential price, you should make sure you can be profitable at that price before you share it with a prospect.

The typical understanding of profit is that it’s “revenue minus expenses.” In other words, it’s what’s left over. That’s a terrible way to determine profit; that’s a good way to ensure you have the thinnest amount of profit possible. If you’re anything like me, this formula doesn’t work. I’m a spender. I love making money and I love spending it. I’ll spend every dollar I have. For years, I was barely ever profitable… not because revenue wasn’t high enough, but because I wasn’t disciplined about expenses. And the strategy of “well then get more disciplined about expenses, idiot” didn’t work for me.

The solution for me was the Profit First mentality from Mike Michaelowicz. In general, the basic idea is to flip the formula from “Revenue - Expenses = Profit” to “Revenue - Profit = Expenses.” Rather than profit being what’s left over—often nothing—profit becomes the first thing you allocate. I was familiar with this idea in regards to personal finance as “pay yourself first” when I read David Bach’s The Automatic Millionaire years ago but never thought to apply it to my business. The genius of this approach is in recognizing that whatever’s left off tends to fluctuate. But you don’t want profit to fluctuate. So set it as fixed instead. We think of expenses as generally fixed, but what if you could set that to fluctuate instead?

In Profit First, Michaelowicz suggests 4 separate categories that revenue tends to be allocated towards, in this order:

- Profit

- Owner’s Compensation

- Taxes

- Operating Expenses

Michaelowicz also suggests standard allocations into each category, depending on the average annual revenue of a business. For example, for a company making $1M–$5M annually, he suggests this allocation as a starting point:

- Profit: 10%

- Owner’s Compensation: 10%

- Taxes: 15%

- Operating Expenses: 65%

To play it out, let’s say you landed a $400k project. Here’s how you would allocate a budget for that project:

- Profit: 10% - $40k

- Owner’s Compensation: 10% - $40k

- Taxes: 15% - $60k

- Operating Expenses: 65% - $260k

Project Value Sheets

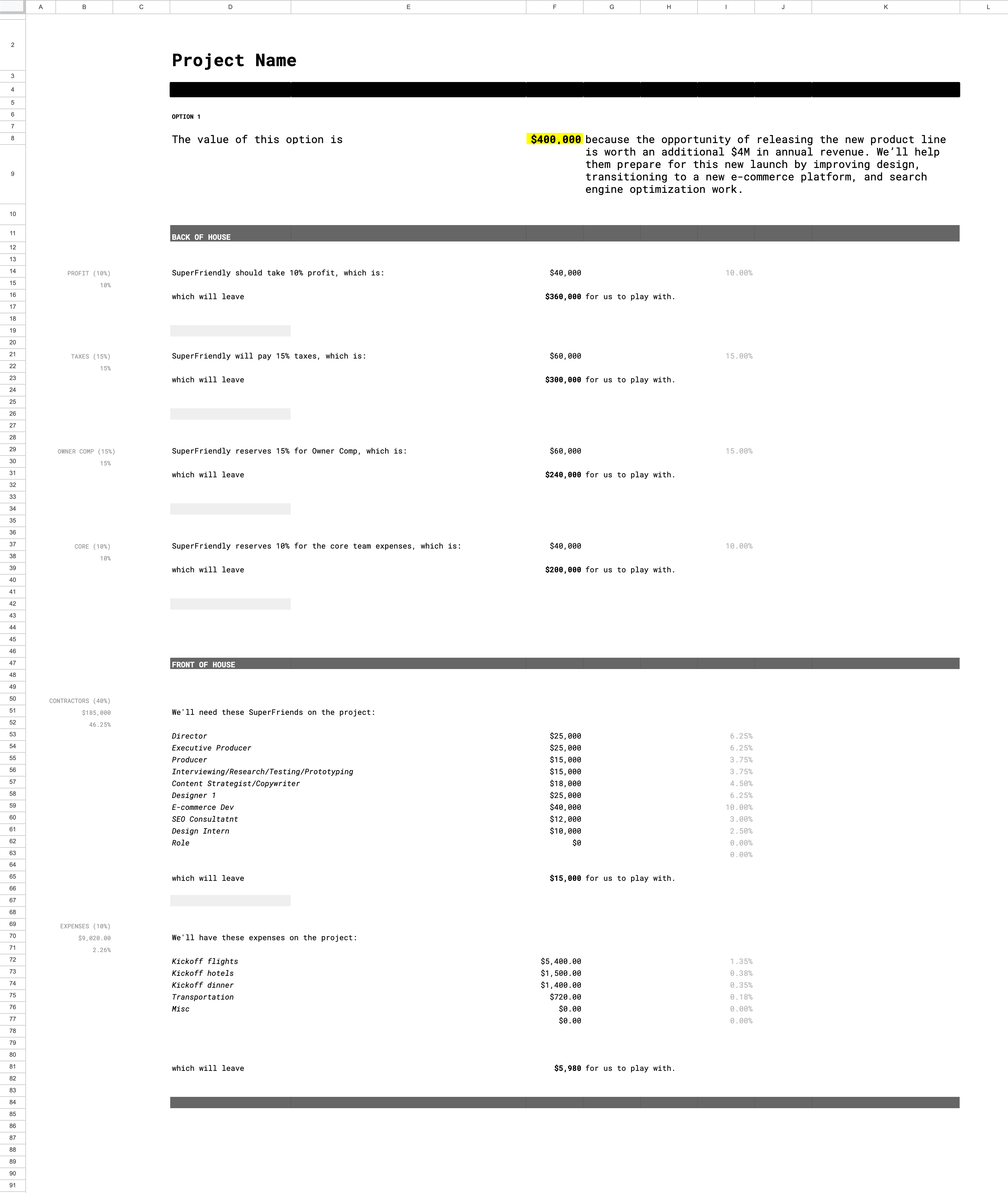

I’ve taken the logic of Profit First and created a spreadsheet we used on every project at my former agency SuperFriendly. We called them Project Value Sheets. Here’s the template you can copy and play around with.

As you can see, I’ve taken the Profit First base and improvised it based on what my agency needed. Here are the major sections:

- The top of the spreadsheet articulates the overall value of the work and how we arrived at it. This is the first number I change.

- Of the next four sections, three follow Profit First: profit, taxes, and owner compensation. I’ve added a fourth category: Core. This has two purposes: 1) to specifically reserve money to pay core members of my team (managing director, executive assistant, accountant, lawyer, etc) even though they were all technically contractors and 2) that the extra 10% makes a round 50% number of a project’s budget that generally goes to the back of the house first. This is the kind of reserved money I’d use to improve the company: sending people equipment, trying out new software, etc. All of these numbers change automatically as the top number changes.

- The front of the house are generally the contractors that would be working directly on the project with the client and the expenses they might need to do their best work, like flights, hotels, software licenses, etc. (For those who don’t know, SuperFriendly’s business model was to assemble a custom team of contractors for every project, so we needed to calculate this every time.)

This kind of set up gave us an easy way to remember our starting guideline: 50% goes to back of house, 50% goes to front of house. It also—in conjunction with the business model—took full advantage of a Profit First mindset: expenses could fluctuate. For example, in a $400k project, I knew I had $200k left for contractors. Could I make that work? If I needed a designer and an engineer, I couldn’t spend $150k each. Instead, I’d have to find a designer and an engineer who would and could do the work required for $100k each or less.

Where this really came in handy was on smaller projects. What if we took on a $25k project? I’d have $12,500 for contractors. If I needed a designer and an engineer, I’d have $6,250 for them each. Could I get a world-class designer for that? You might think not, but I could—at the right scope. A world-class designer in the world might say, “I’d do it for $6,250 if we could limit the work to 1 revision and we kept the project to 2 weeks max.” Then my job as the architect of the project would be to build those constraints into the way we did the project. Voila: I now have my world-class designer in a way that works with my budget.

This is the kind of stuff that turns project architecting and estimation into a creative exercise, not rote multiplication. You can be as creative as you want and get the numbers to play nice if you think of your expenses as flexible and your profit as fixed. What I love about this approach is that it gives me as a spender the permission to spend all the money without worrying because all the important stuff is already paid for. It turns the question into “How much can I spend on this?” instead of “how much can I not spend?,” and that nuance makes all the difference. When every project is profitable, the higher the likelihood that the entire company is profitable.

In the next post, I’ll go over the final step of the sales process: turning a profitable price that a client agrees to into an agreement, and I’ll walk you through my open-source contract line-by-line.

Join 66,800+ subscribers to the weekly Dan Mall Teaches newsletter. I promise to keep my communication light and valuable!