This last week especially, my social media feeds have been full of people talking about how their work in design and tech relate to the amount of money they make and earn. I’m a big proponent of talking openly about money, as I think it helps to surface possibilities to people that they may have not imagined for themselves otherwise. My biggest gripe about how people talk about money is that they often leave out one of the most important parts: context.

This week, I made my contribution to that conversation by finally publishing something I’ve been meaning to for a while now: my salary and income details over the last 19 years of my career.

More importantly, I added some context to each job so it was more than just a table of numbers. Still though, there’s a lot more context to share that was missing. I’d like to share some more of that context here.

One of the pieces that seemed to resonate most were these lines:

Making $10k while staying up late is so different than making $10k while you sleep. Numbers don’t lie, but they don’t always tell the whole story. There’s a such thing as good money and bad money, even if the amount is the same.

I’d like to tell a few more stories about some of the numbers here.

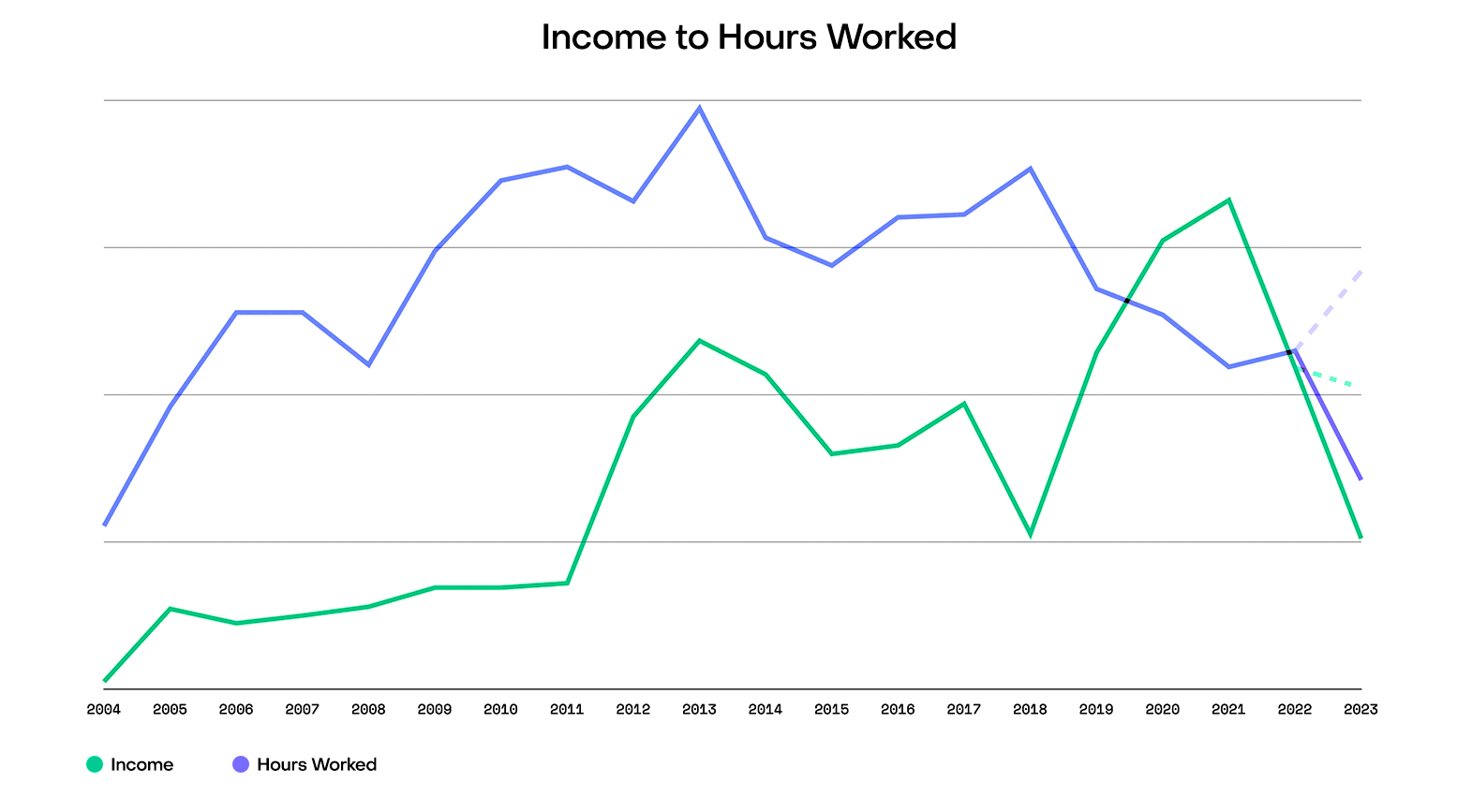

Income to Hours Worked

I think one of the assumptions that comes with sharing annual salary/income numbers is that you’ve worked as hard or much as humanly possible for the most amount of money you can make. Let me be clear: I rarely was. That’s not to say I wasn’t trying to do a good job—I was—but I was also trying to optimize for having a good, challenging job that I enjoyed with enough time to enjoy other people and activities in my life. I wasn’t trying to get rich. (More on that in a minute.)

Here’s a relative-scale graph that shows how much money I made vs. how much I worked each year.

This pulls in decades of data from the accounting software and time-tracking software I’ve used. I’ve never actually looked at this data this way until writing this post. A few things worth pointing out:

For the most part, the first half of my career seems to show that the more I worked, the more money I made. The most significant deviance to that came in 2018 when I worked almost as much as I ever had but made significantly less than I had in a long time. In retrospect and according to this chart, that seems to have started a mindshift that working more isn't related to earning more, and you can see that I immediately started to work less over the following years.

Related, 1-2 years later, I experienced a bit of a flip where I was earning more than I ever had and working less than I had in about a decade. Living the dream, right?! It would have been, except that was probably when I was the most burnt out in my career. More on that in the next section.

Optimizing for money—or not

Back to the point about not optimizing for getting rich. For most of my career, even to this day, I’ve been intentionally focused on other things like growing my skills and learning new things. Otherwise, I think I would have made some different decisions.

One in particular comes to mind.

My wife (Em) and I got married in 2008. Both having lived in Philadelphia for most of our lives to that point, we decided it was time for a new adventure together as a newly married couple. I interviewed at a few places and got enticing offers back from 2 places: digital agency Big Spaceship in Brooklyn, New York and Facebook in Palo Alto, California.

My interview experiences were very wildly different.

Facebook flew my Em and me to Palo Alto for the weekend, rented us a car, and gave us a spending stipend. I did a 6-hour interview loop, including a little bit of time with Zuck. We had a team dinner with the entire design team I would have been working with. They treated me with such respect and kindness, and I got the sense they were all a bit impressed with me and excited to have me on the team. As Em grilled them about their outside-of-work activities, they mentioned intramural Facebook sports teams and frequent weekend hackathons.

In my Big Spaceship interview, I first talked to an associate tech director. As I presented my work, he told me pretty candidly that my stuff wasn’t nearly as good as the other art directors there, and I might have trouble hanging with them. Then I met with 2 art directors who did little more than grunt and shrug as I walked through my work. Lastly, I interviewed with the CEO, who was very polite but seemed to signal that he wasn't sure if I'd be as much of a benefit to the company as a liability.

Facebook extended an offer for $150k plus equity and benefits. Big Spaceship extended me an offer for $80k, and I had to start in less than a month.

As Em and I considered the options, it felt like I’d be making way more money at Facebook but also working all the time (which reinforced my experience at the time that more money only comes with more work). We agreed that conditions for taking the Facebook job was that we’d give it three years and after that, work had to take an intentional backseat so we could play with all that cash for at least three years afterwards. Big Spaceship was one of my dream jobs for such a long time. Seeing their early Nike work was partly what made me want to get into digital design in the first place. Call me a masochist, but I was motivated by the fact that they weren’t impressed by me. I liked the fact that I was an underdog and would really have to prove myself to get respect. It felt like a place where I could grow my skill exponentially by working hard but still have a life outside of work.

I accepted the Big Spaceship role and we quickly moved from Philly to New York in just a few weeks. That tech director (Jamie) that gave me such direct feedback is one of my best friends. The CEO (Mike) who questioned my contribution potential became one of my best mentors, and to this day, I still I call him anytime I need some career advice. I wouldn’t have been able to start SuperFriendly without the experience I got at Big Spaceship.

A few years ago while driving, I was listening to the first lecture in OpenAI CEO’s Sam Altman’s “How to Start a Startup” series called “Why to Start a Startup.” He was scrutinizing the idea that people can have more impact and make more money at their own startups vs. joining an established one. He said, “Even if you joined Facebook as employee number 1000, so you joined like 2009…” and my years perked up, because that would’ve been me. He finished the thought:

Even if you joined Facebook as employee number 1000, so you joined like 2009, you still make $20M… That's how you should be benchmarking when you're thinking about what you might make as an entrepreneur.

I immediately pulled over to the side of the road, shocked. I called Em immediately, and we had a good chuckle over it.

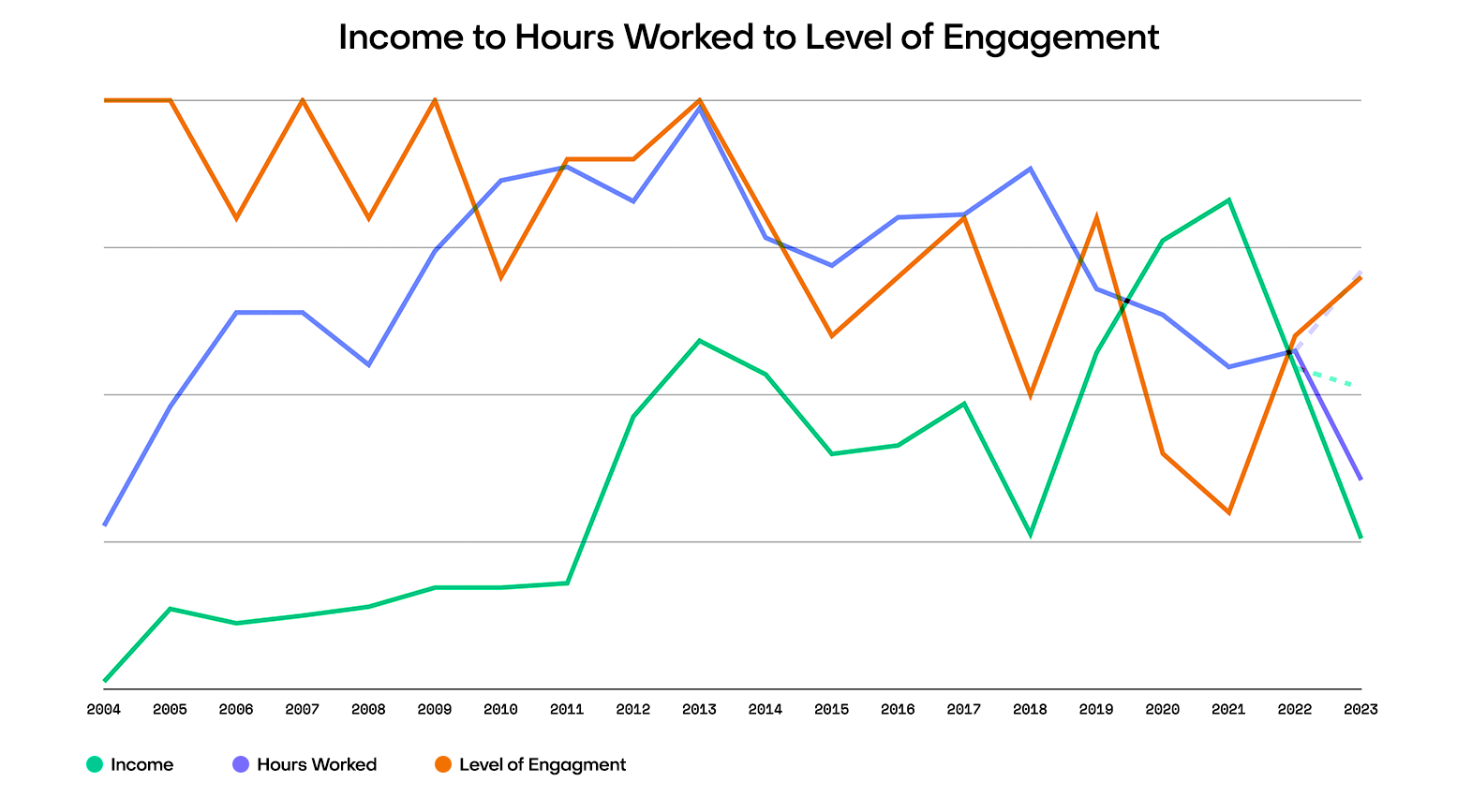

Income to Hours Worked to Level of Engagement

One more piece of context to layer in here: finding a balance between how much you can earn against how little you need to work is important, but how engaged are you? A lot of the reason my feeds have been talking about design is the proliferation of all the tweets saying things like, “I make $1M ARR with 0 employees and work only 2 hours/week.” It sounds like a dream come true! What I wonder is: how much do they love that? If they love that, they truly are living the dream. But I don’t exactly accept that it’s a good thing by default, mostly because I have an opposite experience.

From 2019–2021, SuperFriendly’s total revenue was $5,032,251, which is more than we’d ever grossed in a three-year period. I personally made $1,082,270 across that timeframe; that’s Monopoly money, more money than I’d ever made in that amount of time. I was working the least I had in a long time… about 30 hours/week or less. I was also burnt out. But not from overwork, as you might expect.

This was the timeframe that I decided to experiment with scaling SuperFriendly. Together with my team, we scaled to our largest amount of concurrent contractors (70) and concurrent accounts (28). I just… didn’t care. Profits were dwindling. More importantly, we weren’t really moving anything forward in our mission to “create better opportunities for people who wouldn’t have them otherwise.” I reflected on this more in my SuperFriendly 2021 wrap-up.

Psychologist Herbert Freudenberger coined the term “burnout” in 1975 and defined it as:

- Emotional exhaustion: the fatigue that comes from caring too much, for too long

- Depersonalization: the depletion of empathy, caring, and compassion

- Decreased sense of accomplishment: an unconquerable sense of futility or feeling that nothing you do makes any difference.

I cared about what we were doing at SuperFriendly a lot. As I moved farther away from client work, I moved farther away from our SuperFriends, so my work was definitely much more depersonalized. As a result, I didn’t feel like I was accomplishing anything. I spent most of my time coaching our Directors and Producers, but that didn’t seem to help or hurt anything. I think the combination of these things is why I was burnt out.

Or was it because there was a MASSIVE. GLOBAL. PANDEMIC. happening during this timeframe? I don’t think I’ll ever be able to decouple these things.

It’s easy to look at money out of context. Was it worth it to work 20-30 hours a week for 3-years and make 7 figures? Of course! I’d do it again 100 times over. But was it worth it to 20-30 hours a week for 3-years and make 7 figures while being emotionally exhausted? With that additional context, I’m not sure I would do it over again the same way.

Read Next

Consent to Proceed

Join 62,700+ subscribers to the weekly Dan Mall Teaches newsletter. I promise to keep my communication light and valuable!