Our industry doesn’t do a great job of mixing learning with working. We setup things like weekend hackathons, afterwork programs, and “lunch and learns”—all great endeavors, but their very existence proves that we think of learning as a separate thing from work, that work doesn’t provide ample enough opportunity to develop new skills.

Writer and educator David Edwards laments the typical American school system setup in Wired article On Learning by Doing:

We “learn,” and after this we “do.” We go to school and then we go to work… This approach does not map very well to personal and professional success in America today. Learning and doing have become inseparable in the face of conditions that invite us to discover.

The separation of learning and doing is partly due to our incessant quest for maximum efficiency in the workplace, which is sometimes synonymous with the elimination of failure in the workplace. In her article Strategies for Learning from Failure in the Harvard Business Review, Professor Amy Edmondson describes a spectrum of reasons for failure, with blameworthy types of failure on one end and praiseworthy types on the other. Certainly, we don’t want our coworkers to fail because of deviance or attention, but the elimination of failure unfortunately removes the opportunity for failure through exploratory testing or uncertainty, which are crucial in creative process.

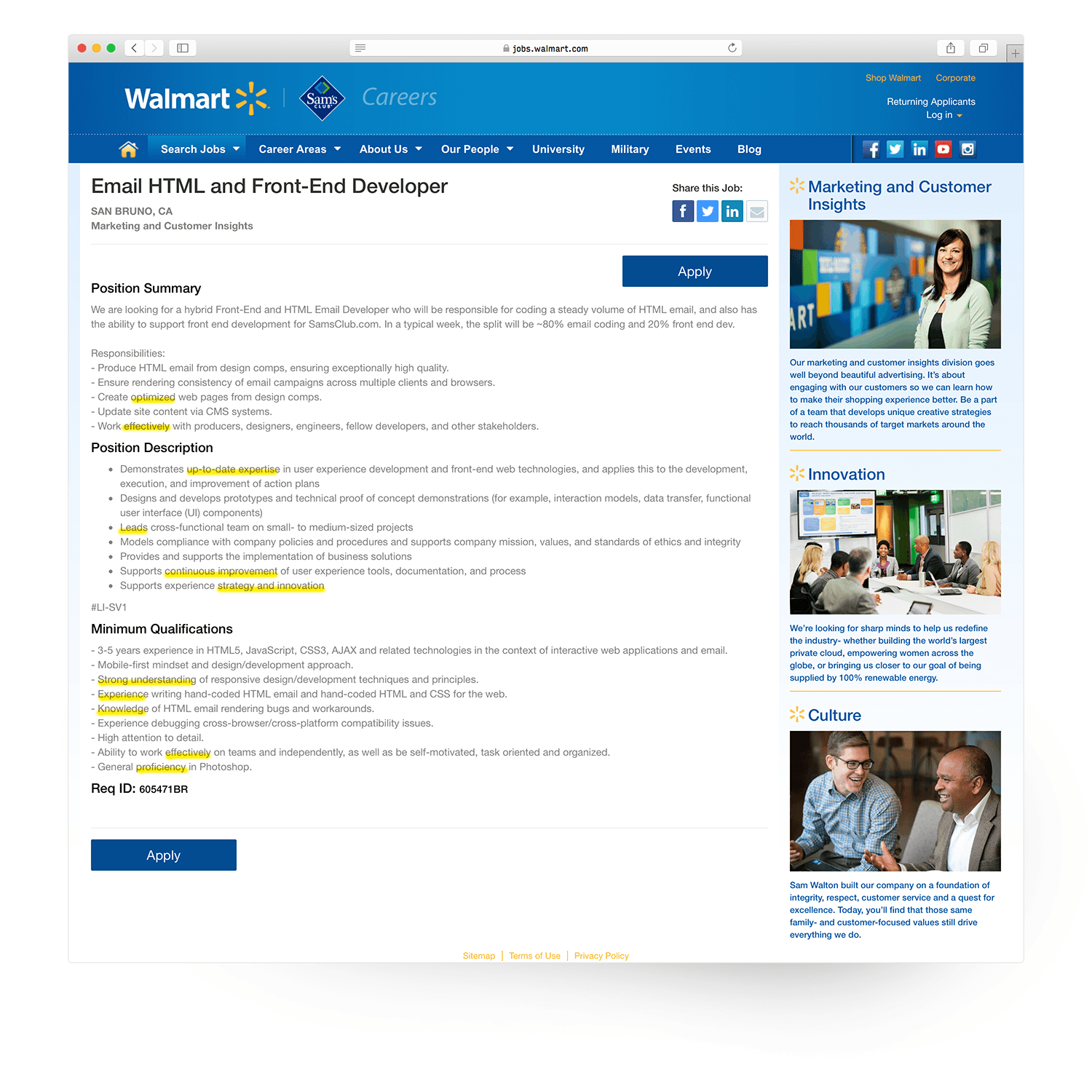

Consider the way we hire. Our job pages are strewn with solicitations for “extraordinary people,” prior work of “high quality,” an enthusiasm for those who can “champion ideas,” and countless other superlatives. The subtext is clear: you must be amazing before we hire you, because you certainly aren’t going to gain those skills here. The prerequisite for greatness is as crippling as it is sparse.

And for good reason. Imagine a job description that sounded like this:

We’re looking for a designer that’s a bit of an underachiever, someone fairly average.

No skills required.

Don’t worry about being a self-starter; if you can follow orders, that’s good enough for us.

This wouldn’t go over very well. Or would it?

Bridging the gap

Let’s look at a few statistics:

- In the 2012 report “A National Talent Strategy” (PDF—1.7MB), Microsoft reports that “the country’s higher education system is currently producing only 40,000 bachelor’s degrees in computer science annually.”

- According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 1 million programming jobs in the U.S. will go unfilled by 2020.

- According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, there are 7.9 million unemployed in the United States as of April 2016.

As a scatter plot measured against a spectrum or skills, that may look something like this (approximation—not drawn to scale):

In looking to fill vacant job openings, many tech companies look to the upper echelon of this graph. That results in the skilled becoming even more skilled as they move from job to job, creating a wider gap between those at the top and those at the bottom.

I believe there’s a great solution to bridge this ever-widening gap, and it’s called apprenticeship.

About apprenticeship

Wikipedia defines apprenticeship as “a system of training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study.” Apprenticeship originated in medieval times and were largely governed by guilds.

Here’s how a blacksmith apprenticeship would work in those times. A parent would indenture their child—little Johnny, typically around 10 years old—to a local master blacksmith. Johnny would live with the blacksmith for about 7 years, learning the trade of blacksmithing but also learning the business of blacksmith, as well as life skills like cooking, cleaning, and generally how to function in society. Teaching all of these responsibilities were under the purview of the blacksmith, not just the craft. The blacksmith was responsible for teaching Johnny how to be a professional. This grooming of professionalism is what’s missing in the common internship today, which is why I believe in apprenticeships as a more productive model.

(For a deeper dive, interaction designer Ivana McConnell has written “Apprenticeship, an internship replacement,” a fantastic essay about the apprenticeship model.)

Apprenticeships are common among many different professions:

- Many tattoo artists break into that profession through apprenticeship. Pittsburgh tattoo artist Jason Lambert wrote an amazing list of do’s and don’ts for aspiring apprentices that’s definitely applicable outside of the tattoo world.

- Many chefs start out as apprentices. The Apprentice: My Life in the Kitchen is a memoir from chef Jacques Pepin about his start in the culinary world.

- Apprenticeship is extremely common in the field of architecture. Frank Lloyd Wright’s Letters to Apprentices collect the way the master architect relayed his genius to those who worked with him.

- Famed theologian Martin Luther recorded a series of informal conversations he had with apprentices and other dinner guest in the book Table Talk. They discuss theology, government, beliefs, academia, and much more.

The design and development industry is full of internships that intend to teach good design and development practices, but it’s extremely limited in apprenticeships whose purpose is to create well-rounded professionals.

About SuperFriendly Academy

Since December 2012, I’ve been silently—and sometimes not-so-silently—running SuperFriendly Academy, a web design & web development apprenticeship that teaches both core skills and professionalism, but leans more toward the latter. It’s a 9-month program, created for people who have little to no experience with design or development but are looking :

- Months 1–3 are basic training. Because everyone who goes through this apprenticeship knows very little about the craft of design or development, this first quarter gets them up to speed. On the first day of an apprenticeship, we talk about things like what a URL is and how the web works in general. For design apprentices, we walk through the toolbars of Sketch and Photoshop, one tool at a time to talk about what they do, For development apprentices, we start by talking about the anatomy of HTML tags. And the curriculum builds from there, getting more and more tailored to the individual as we progress.

Before we even get to this point, I also ask each apprentice to save enough money to pay for about 3 months of their expenses. I don’t pay apprentices to start, because they’re not valuable to me at this point since they don’t have much knowledge about this world yet. I don’t ask them to pay to go through the apprenticeship, so we both break even. Because this is likely the first knowledge work job an apprentice may have had, it tends to be mentally taxing, thereby making it fairly difficult to maintain a part-time nights/weekends job while doing the apprenticeship. This 3-month savings request is often where I see interest wane, because not everyone can afford to forego income for that amount of time. (I’m working on ways to solve this problem to make this apprenticeship more feasible for more folks. If you have suggestions on how I can better do that, please let me know.) - Months 3–6 are about practice. By this point, the apprentice has enough of an understanding of design and/or code that I can start putting them on client projects. We start small; a typical first paying assignment for an apprentices might be to design or code a very small section of a site or app, like a footer or a search interaction. This work is always supervised by someone who is ultimately responsible for the quality of that work, either myself or another SuperFriend. Because some of the apprentices go on to freelance after their apprenticeships are over, I treat them like subcontractors on all projects. I ask them to price those projects for me as if I was hiring them as a professional, and we work together on discussing what good pricing looks like if they under- or overbid. The more their skills increase during this timeframe, the bigger responsibilities I can assign to them, and the more they get paid. This time period is crucial in teaching the most important parts of professionalism. Almost every apprentice picks up the design and code stuff really quickly, but some of them flop with softer things like meeting deadlines, setting expectations for colleagues and clients, articulating their work well, and other similar skills.

- Months 6–9 are about job readiness. The previous months were mostly about practicing professionalism and amassing skills and projects, and now it’s time to turn those things into a launchpad. We make lists of the places the apprentice might want to work, and we start preparing portfolios targeted at those places. We do mock interviews to get them ready for the job they’ve worked so hard to get. I help coach them through negotiating salaries to make sure they’re landing in the right place with the right setup.

Why have apprentices?

While you may be sold on the altruism of taking on an apprentice, you may be having trouble seeing what’s in it for you or your company. Fortunately, there are many benefits to investing in an apprentice or even an apprenticeship program:

Fishing in a larger pond

From a pure numbers perspective, you have lower odds of finding a new hire in the highly competitive market of 40,000 computer science graduates than you are the 8 million unemployed people in this country. The pool is simply larger.

Cost-effectivness

It’s also way cheaper. Compare the numbers of poaching a highly competitive candidate vs. giving an accomplished apprentice a chance (these numbers assume a 5% annual raise):

| Experienced Designer | Apprentice | |

|---|---|---|

| Year 1 | $80,000 | $40,000 |

| Year 2 | $84,000 | $42,000 |

| Year 3 | $42,000 + new job search | $44,100 |

| Total | $206,000 | $126,000 |

For one, the competitive candidate will come in at a more demanding salary and is likely to continue job hopping after year 3. After that time, you may have to deal with your more competitive candidate leaving, which means you’ve lost a good bit of institutional knowledge and also have a hefty replacement search ahead of you.

Less investment than you may think

As you consider the amount of time you may have to spend training an apprentice over 9 months, you may be skeptical about being able to carve out that effort. But, it’s probably less time than you think.

I’ve had ten apprentices under this curriculum, and, on average, the amount of time I’ve spent training each of them over 9-months is only 35 hours. That’s about 4 hours/month, 1 hour/week, or just 12 minutes a day. That’s right: pretty doable for just about anyone, even taking into account a busy schedule.

(The big caveat with these numbers is that it doesn’t include the amount of time I spend on direction within a project, but, because that time is project-specific, it’s work I would have done anyway directing anyone on the project team, so I don’t count it as general training time.)

Regarding money, the average amount I’ve paid to an apprentice over 9 months is $7,000. That’s about $1166/month, $292/week, $58/day, or $7/hour. That’s pretty affordable for many organizations. And for apprentices, choosing between minimum wage for a food service job and one that helps them invest in their future, I’d guess that choice is a no-brainer.

Diversity

Perhaps the most important reason to invest in training the untrained is that that pool of folks likely doesn’t look like you, think like you, work like you, or do much like you. And that’s an incredible thing. There’s so much sameness that exists in tech today, and that’s undoubtedly leading to the unoriginal and uninventive sea of products we see today. Intentionally investing in different perspectives can work wonders for every organization.

Don’t take my word for it; the very tangible results speak for themselves. In their article Why Diversity Matters, McKinsey & Company reports that gender-diverse companies are 15% more likely to have financial returns above their respective national industry means, and racially- and ethnically-diverse companies are 35% more likely to have financial returns above their resurrecting national industry means. Apprenticeships aren’t just an altruistic endeavor; they can directly impact your bottom line.

Join the cause

The great news is that there are already many apprenticeships out there for budding designers, developers, and UX professionals. The Nerdery runs an amazing UX Design apprenticeship, led by Fred Beecher. Fresh Tilled Soil runs a 15-week AUX program, which they just graciously open-sourced. Sparkbox runs a 6-month apprenticeship. Thoughtbot runs a 3-month apprenticeship. Huge runs a 12-week UX school.

As of right now, SuperFriendly Academy is open for applications. Head over to the site and get in touch if you meet the guidelines.

There are already great programs out there like this, but there aren’t nearly enough. It’s about time that changed.

Read Next

Selling Design Systems

Join 62,700+ subscribers to the weekly Dan Mall Teaches newsletter. I promise to keep my communication light and valuable!