As a kid growing up in the late 80s and early 90s, my life outside of school consisted of drawing, watching cartoons, and playing/watching basketball. I was a big fan of Michael Jordan—who wasn’t at that time?—and anything with a Nike logo on it was the epitome of cool. The iconic “Just Do It,” “Mars Blackmon,” “I Am Not a Role Model,” and “Bo Knows” ads were bold, creative, and played in mind non-stop. I wanted so badly to wear some Air Jordans, Air Griffeys, Uptempos, Air Max Plus, Penny’s, Pippen’s, or any of the popular sneakers at the time. But these were hundreds of dollars, and that was definitely not in the budget for our lower middle class family in north Philly. The only Nikes my mom took me to get once a year was from the clearance rack at Kmart. I was still grateful, but one day, I wanted to fully embrace the Nike culture I admired so much. Somewhere within the Chicago Bulls’ NBA championships from 1991–1998 as adolescent me was learning Photoshop and Flash and FrontPage and starting to dream about career choices, I figured Nike would be a cool place to work.

Nike work

Fast forward to 2006. I was in my senior year at college, heavily steeped in a digital design education, I came across one of the best websites I had ever seen to this day: the brand new Nike Air website.

There was video, animation, visual effects, sound… it was like a movie, but in a web browser. I was sold: I wanted to make stuff like this for my career. I had to work for Nike. I made some soft plans to find my way to Beaverton, Oregon where Nike was headquartered so I could work from the mothership.

In my research, I eventually realized that Nike themselves weren’t always responsible for doing the cool work I’d seen for years, but that they hired agencies to make this stuff for them. That shifted my thinking: maybe, instead of working for Nike, I could work for the agencies that made this stuff for them. I was in luck: I already had an internship at a web design agency (the now-defunct Pixelworthy), and later that year, I would be one of the founding members of the Philadelphia office of Happy Cog.

The problem is that Nike wasn’t one of our clients. Far from it, actually, at least in my opinion. If I wasn’t working for Nike, I could settle for Adidas, or other sportswear companies, or other big brands at least. But our first few clients were places like small production house Paramount Vantage or indie gaming publisher Kongregate or Irish culture center Comhaltas. And we weren’t crafting big ad campaigns for these companies; we were building a few dinky web templates for them.

I complained to Jason, my creative director. “Why don’t we get clients like Nike?”

“What’s ‘a client like Nike?’” he asked.

“Clients that have lots of assets for us to work with, with big budgets and generous timelines where we can make things really immersive.” I retorted.

Jason replied with wisdom that has stuck with me for years, something that I think about on every project I work on to this day. “Nike’s not going to come to us because we’re not doing work that already looks like Nike. Start making that work with our current clients without all the big budgets, fancy assets, and long timelines, and the Nike work will come. Work on your work now as if you were working for Nike.”

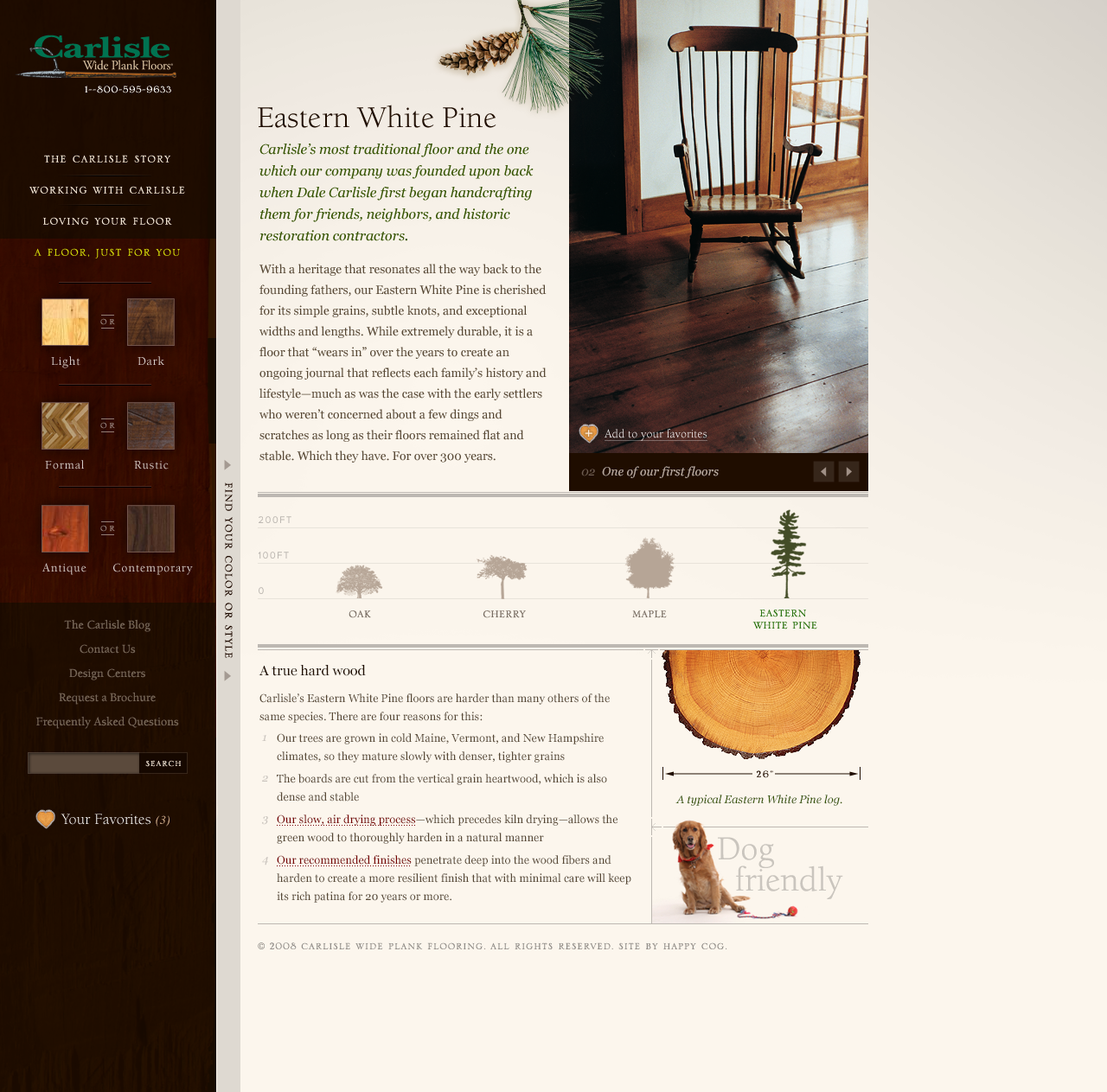

The next project that came up was a website redesign for Carlisle Wide Plank Floors. I initially did a boring design, as I was thinking “standard e-commerce website.” My boss Greg, knowing my wishes, pushed my thinking. He encouraged me to think less of it as designing a website and more about designing your dream home. “Make it experiential,” he said. “How would Nike make you design your dream home?”

I thought about things like Nike ID, where you could customize your own pair of sneakers and explore a sneaker model in 3D space with the choices you made. At the moment, I didn’t have the skill, the time, or the ambition to build my own 3D models, but I did have the ability to do some heavy Photoshopping and had access to lots of great photography from the client, so I evolved my direction to be much more photographic and interactive.

The client ultimately didn’t choose my direction, but this project gave me confidence that the only limit on my work was what I could come up with, not the budget or the client or the timeline or the assets. I started slowly investing in and growing my ability to create my own assets, from photography to motion to illustration. I tried to bring as much of that approach to all of our work for clients like ADP, Liberty Mutual, Housing Works, MICA, and more.

Do what I do best

Somewhere along the way, I learned that the Nike Air website I had admired for all those years was created by an agency in Brooklyn called Big Spaceship. I tracked down and pored over a few of their case studies and attended events and talks from several of their employees. I became a big fan.

Eventually, I got a job at Big Spaceship, and many of the people who worked on that Nike Air site became mentors, colleagues, and friends. I went there to learn how to make sites like Nike Air, and honestly, I struggled. I remember trying to make a site for GE my Nike Air; it wasn’t. I tried to do it on some projects for Wrigley; it didn’t work. In fact, my boss Mike called me into his office one day to talk to me about my sub-par performance. He didn’t mince words that my work wasn’t up to snuff. But he also gave me these words of encouragement: “While we do want you to learn how we’ve done things, we hired you so that you could bring what you do really well to the table.”

That guidance changed my outlook again. Instead of trying to design everything with visual effects and particle systems and motion graphics, I approached my next project—designing the Star Wars website—with what I did well: bold typography, tight grid systems, and solid platform design. I knocked this one out of the park. Building momentum, I carried it forward on my next big project: overhauling Crayola’s entire digital ecosystem. These were some of my first big efforts in learning and architecting design systems, even though I wasn’t thinking of them as such at the time.

Eyes on the prize

I started my own agency SuperFriendly shortly thereafter, and I kept the “do this project as if you were doing it for Nike” mentality in all of my work for a dazzling and humbling directory of clients like Apple, ESPN, Mastercard, Google, AOL, Time Inc, The New York Times, Canon, Aetna, Dotdash Meredith, ExxonMobil, Harvard, FX, Khan Academy, Carnegie Mellon University, Toast, United Airlines, The Philadelphia Inquirer, Pfizer, Herman Miller, The University of Pittsburgh, Twilio, Peloton, and more. And yep, I'm listing all of those to brag, because I’m super proud of that list. All the while, I’d been developing a specialty and a reputation in design systems. Nike wasn’t on that list, but it wasn’t for lack of trying. I had several friends who ran their own agencies that had Nike as a client. I volunteered many times to all of them to act as an intern for free on any of their Nike projects anytime, but no one ever took me up on it.

A lot of that work over the years won me a few shelves worth of design awards, which also resulted in being asked to sit on a few award juries. In 2019, I was invited to be on the jury of that year’s Communication Arts Interactive award show At the Communication Arts office, among the other jurors I met was Hayley Hughes, then a UX manager at Shopify. We bonded over mutual friends and connections as well as an appreciation for the grind of design system work. Two years later, I saw Hayley announce on social media that she got a job as a design director at Nike, working specifically on design systems. I sent her a note to congratulate her and express my jealousy that she had my dream job. Three months after that, Hayley sent me a message that said, “Soooo, it turns out that we’ve got an upcoming design systems project at Nike that I’m hoping might be a good fit for you and your friends at SuperFriendly.”

After breezing through some paperwork, I’m proud to say that I finally got to do my dream project with my dream client in 2021, spending a few months working a team of 30 of Nike’s best and brightest designers, engineers, and product folks to reignite their design system practice.

I built my first website in 1998, and I worked with my dream client in 2021. I just spent about 1500 words telling you about the winding, 23-year journey that got me there. While there’s a small part of me that wishes it would have happened 20 years sooner, I’m more glad that I was able to take the scenic route there. In a lot of ways that I hope you can see through my story, a project with Nike was always the destination in some form, but I’m happy that I didn’t make it the one and only stop. The small projects I was complaining about still had big moments within them. Kongregate was the first VC-funded project I worked on that then got acquired for $55 million. Comhaltas enabled me to take a trip to Ireland where I proposed to Em on a horse & carriage ride through Dublin. I worked on a billion-dollar rebrand. I tried kolaches for the first time with ExxonMobil. I designed an iPad app that controlled a 10,000-pound robot arm to move furniture around a room. I helped make travel better for United Airlines customers. I sat at a high-rollers table at The Cosmopolitan when I worked on their rewards program. I made resources for restaurant owners with Toast.

So yes, identify your dream client and take the steps you can to work with them, but do give yourself the liberty to meander on your way there. En route to your dream project, you may end up having a dream career. I did.

Read Next

Creating Portfolio Pieces

Join 66,800+ subscribers to the weekly Dan Mall Teaches newsletter. I promise to keep my communication light and valuable!